Central Park Casino

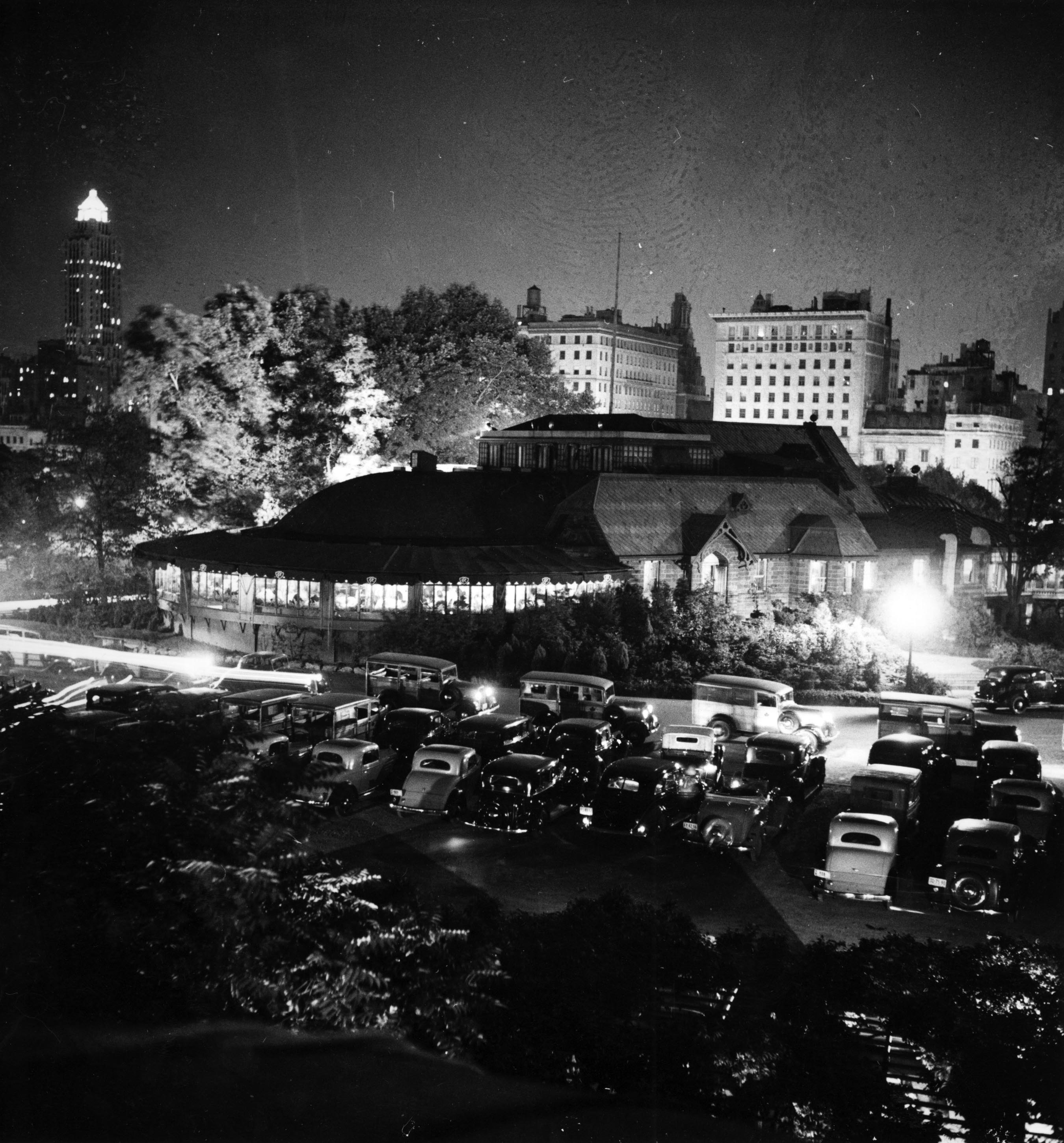

It’s the hottest nightclub in Manhattan on a Saturday night with limos lined up for blocks. Glowering doormen carefully check the guest list before admitting the tuxedoed and bejeweled monarchs of New York society. The décor is all black glass and dark, glistening dance floors, with a sumptuous dining room and not one, but two of the hottest musical acts in New York. Money and power are well represented and very much attracted to one another as Wall Street mixes with Broadway and Hollywood, with a soupçon of Runyonesque mug shots for color. It’s 1930 and the place to be is the Casino in Central Park.

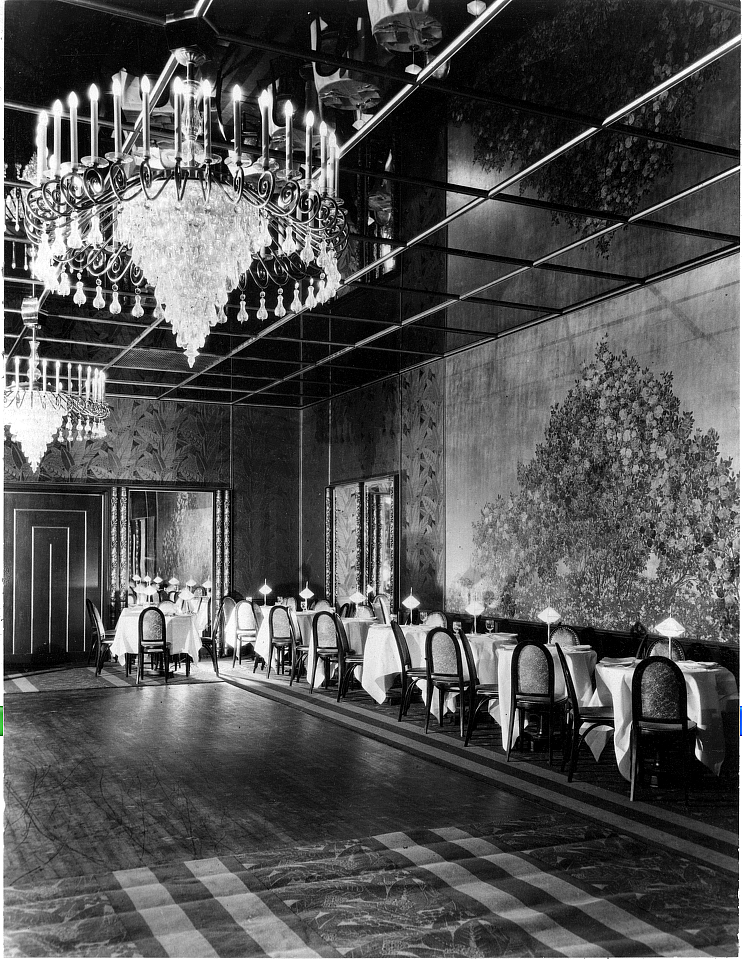

It’s the hottest nightclub in Manhattan on a Saturday night with limos lined up for blocks. Glowering doormen carefully check the guest list before admitting the tuxedoed and bejeweled monarchs of New York society. The décor is all black glass and dark, glistening dance floors, with a sumptuous dining room and not one, but two of the hottest musical acts in New York. Money and power are well represented and very much attracted to one another as Wall Street mixes with Broadway and Hollywood, with a soupçon of Runyonesque mug shots for color. It’s 1930 and the place to be is the Casino in Central Park.

The Casino restaurant on the east side of the Mall near 70th Street had “never been noted for catering to the poor,” the Times dryly observed in 1929, but that year the restaurant became even more exclusive when it was transformed into a nightclub for New York high society.

It was, in effect, a gift from former song writer Jimmy Walker, elected mayor in 1926, to his friend Sidney Solomon, who had been in the hotel business and won Beau James’s affection by introducing him to his tailor. Walker had asked Solomon if there was anything he could do for him in return. As a matter of fact, Solomon replied, “I’d like to take over the old Casino in Central Park and make it an outstanding restaurant.” City lawyers evicted the Casino’s prior licensed operator in February 1929. To oversee his enterprise, Solomon promptly appointed a board of governors comprising prominent New York business and social leaders. Heading the board was Anthony Drexel Biddle, Jr., millionaire scion of the socially prominent Philadelphia clan and a friend of the mayor’s. “We feel,” Biddle explained, “that New York needs a dining place around which the cultured life of the city can rotate. … It will give Central Park a touch of the life and color that has been lacking for a number of years.” Even before the Casino had opened, former mayor John F. Hylan charged that it represented “a new seizure by royalty of the city property.” Biddle responded disingenuously: “All we wanted to do is something for the public.”

Solomon changed the exterior of Vaux’s original brick and stone building very little, but he recruited the Vienna-born designer Joseph Urban to redesign the interior in modernist style. The Casino would have a tulip pavilion, an orange terrace, a silver conservatory, and a spectacular black-glass ballroom. Walker and his mistress, Betty Compton, both reviewed Urban’s sketches before Solomon spent the approximately $500,000 it took to carry out the renovations. There would be tables for six hundred patrons and parking for three hundred cars.

On opening night, June 4, 1929, “a good deal of cynical talk was bandied about” among the crowd who watched the socialites arrive. In the fall mayoral campaign Fiorello La Guardia attacked Walker for leasing the “whoopee joint” in the park to his close friends for a ridiculously low rent — friends who, in turn, obtained some of their financing from gangster Arnold Rothstein (the man who reputedly fixed the 1919 World Series). The stock market crashed that same fall and federal prohibition agents raided the Casino. The elegant playground of the rich had become a symbol of decadence and corruption. Parks commissioner Robert Moses later replaced the Casino with the Rumsey Playground.

On opening night, June 4, 1929, “a good deal of cynical talk was bandied about” among the crowd who watched the socialites arrive. In the fall mayoral campaign Fiorello La Guardia attacked Walker for leasing the “whoopee joint” in the park to his close friends for a ridiculously low rent — friends who, in turn, obtained some of their financing from gangster Arnold Rothstein (the man who reputedly fixed the 1919 World Series). The stock market crashed that same fall and federal prohibition agents raided the Casino. The elegant playground of the rich had become a symbol of decadence and corruption. Parks commissioner Robert Moses later replaced the Casino with the Rumsey Playground.