The earliest cinematic portrayals of Central Park were almost always romantic in nature. Whether it was the backdrop for joyous singing and dancing, as in “On the Town”, or the setting for sentimental love stories, such as “Portrait of Jennie”, the park was seen as either a place of populist energy or quiet romance. It is interesting to note that before the war, and for the first few years after, there are no movies that use Central Park as anything but a positive locale, one that resonates with the energy and romance of Manhattan. It’s not really until the early seventies that movies, usually comedies, dramatize the darker aspects of the park. It seems that in the middle sixties the park developed several different personalities, especially in the eyes of movie makers. Since then the Park has been generally characterized in movies in one of three ways. First it is seen as a romantic place, almost magical, a metaphor for all the beautiful, creative, fantastic things the city represents to so many people who love it. Secondly it is portrayed as a dark, dangerous and foreboding place, a symbol of urban decay and the decline of civilized society in the second half of the century. Lastly it is used simply as a park, a useful field of recreation and contemplation, simply the lungs of the city.

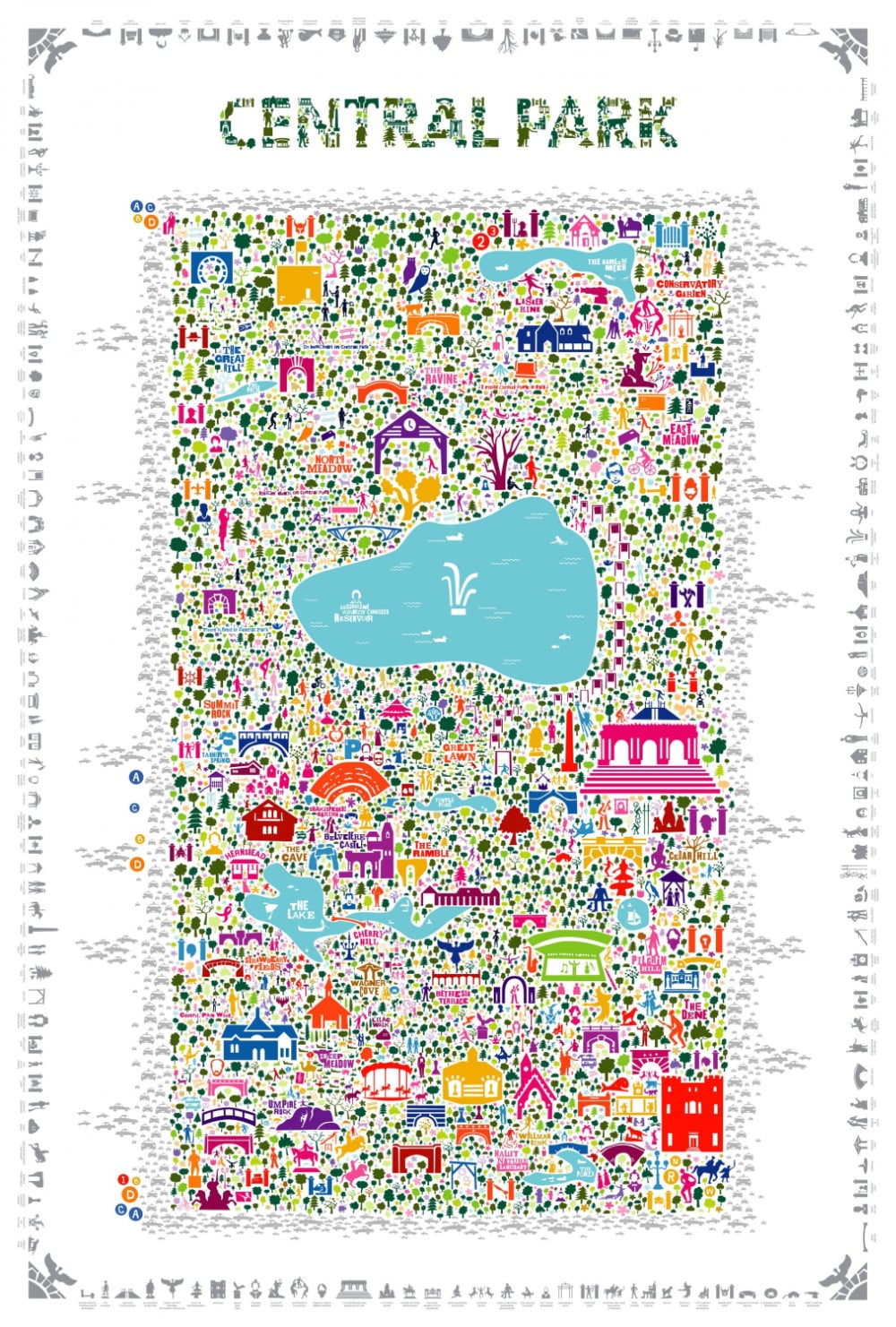

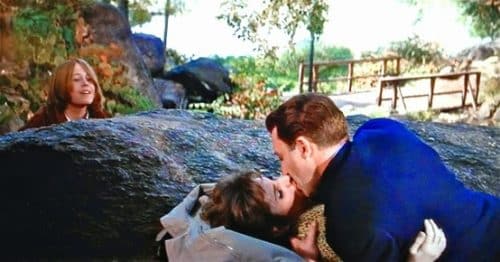

One example of Central Park in its romantic role would be “The World of Henry Orient”, 1964, directed by George Roy Hill. In this movie the park is seen in autumn, a cheerful, pretty landscape that provides the back drop for the afternoon frolics of two young girls, played by Tippy Walker and Merrie Spaeth. It’s the scene of a day long fantasy, chasing over and under bridges, around lakes and statues that bonds the two together. It is also the trysting place of Peter Sellers and Paula Prentiss, which the girls discover to Seller’s everlasting chagrin. Later in the movie, when Spaeth is searching for her missing friend, we see her wondering through a snow covered park, a bleak and barren landscape, all grey frost and frozen ground. But even in this wintry evocation the park is not seen as a threatening place. It is not yet dangerous and unforgiving of intruders.

One example of Central Park in its romantic role would be “The World of Henry Orient”, 1964, directed by George Roy Hill. In this movie the park is seen in autumn, a cheerful, pretty landscape that provides the back drop for the afternoon frolics of two young girls, played by Tippy Walker and Merrie Spaeth. It’s the scene of a day long fantasy, chasing over and under bridges, around lakes and statues that bonds the two together. It is also the trysting place of Peter Sellers and Paula Prentiss, which the girls discover to Seller’s everlasting chagrin. Later in the movie, when Spaeth is searching for her missing friend, we see her wondering through a snow covered park, a bleak and barren landscape, all grey frost and frozen ground. But even in this wintry evocation the park is not seen as a threatening place. It is not yet dangerous and unforgiving of intruders.

The most romantic view of the park is without a doubt the movie adaptation of the musical “Hair”, 1980, directed by Milos Forman. The film opens with an extended version of the song Aquarius that has Twyla Tharp choreographed dancers writhing about the lush autumn landscape along with police horses that prance in step to the music. It is a wild and joyful place filled with hippies and hope. It is their home, a place filled with promise and life, counter culture experimentation and an exuberant challenge to the concrete canyon dwellers that surround it. It is, of course, wildly simplistic and naive, but still it seduces you into thinking that even if it wasn’t exactly like that it should have been. For that matter it convinces you that that is the way it should still be. There are long shots that include the leafy vistas of the fall in New York and upwardly angled cameras that frame each character against the skyline. This is place you wanted to come to when you first heard about New York. It’s a place where people dance and sing and experience life vividly and viscerally. The place you never quite found, the one you still dream about.

In terms of pure fantasy the best example would be “A Troll in Central Park”, Don Bluth, 1994. It’s an animated fairytale about a troll, named Stanley, that is banished to New York City for having a green thumb, the punishment being the assumption that there is no greenery to be found amidst Manhattan’s concrete canyons. Much to his delight, however, little Stanley finds himself dropped in Central Park, in mid spring. The park is drawn beautifully, with a remarkable respect given to geographic detail, and it becomes a final battle ground between powerful forces for good and evil. Of course the forces of good prevail and the park becomes an Eden-like garden in the process.

On the negative side of the coin few movies can come close to “The Out of Towners”, 1970, directed by Arthur Hill and written by Neil Simon. In this film the park is portrayed as an extension of the inhospitable and menacing city landscape that surrounds it. Sandy Dennis and Jack Lemmon are forced to find refuge in the park after a series of increasingly farcical mishaps leaves them shelter less. While in the park they are mugged, attacked by a dog and then accused of child molesting. The picture we have of the park is a litter strewn no man’s land populated by criminals and unfriendly policemen. (It is in fact this unrelenting negativism that ultimately undermines the comedic credibility of the movie. By the end of the movie you’re rooting for dog that steals their crackerjacks.) The park itself is shot in a very unfriendly manner, with dark shadows at night and glaring sunlight during the day. There are no panoramic shots, no fountains or bridges, just old fences and scrawny bushes. It is clearly shown to be an unhealthy environment and a hazardous place at best. In fact it is not only an extension of the dangerous city that surrounds it has come to symbolize it. As far as Simon is concerned the park is the coup de gras of the many misfortunes that befall this hapless, humorless, frumpy couple.

In “The Still of the Night”, directed by Robert Benton, Central Park is shot by night, in the vicinity of The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Roy Shieder is following Meryl Streep and thinks he sees her enter the park. He is in love with her, but of course suspects her of murder, a dating dilema in Manhattan that occurs with a great deal more frequency than you would like to think. He follows her figure into the park and is promptly mugged himself. The really nice twist to this scene is that after the mugger steals Roy’s raincoat he is in turn murdered after being mistaken for Mr. Shieder. (If only life in the big city was always this symmetrical.) In this case the park is seen as both romantic and dangerous, a place of intrigue and allure, although certainly still not one that you would like to visit after dark.

The ultimate portrayal of Central Park as a dark and dangerous place is undoubtedly that of “Where’s Papa?”, directed by Carl Reiner. It was released in 1970, the same year as Neil Simon’s “Out of Towners”, and carries the depiction of Central Park as a battle zone of urban violence to a hysterical degree, although probably not far from the truth in the eyes of most of the rest of America. George Segal lives with his senile mother on the Upper West Side. Ron Liebman lives with his family on the Upper East Side. George Segal calls his brother and to inform him that if he doesn’t come over and get Mom, thereby leaving George at home, alone, with his date, he is going to drop her out the window. Obviously Ron Liebman is in a great hurry to get there so he decides, rather illogically, to run directly across instead of taking a cab. This has apparently happened many times before and each time Mr. Liebman has been mugged. This time is no exception. Half way through the park Mr. Liebman’s character, Sidney, is accosted my four young men (One of whom is played by a young Garret Morris, pre SNL). They all recognize each other from his previous attacks. This time they decide to reenact a scene from the movie “Naked Prey”. This results in Sidney arriving at George’s without a stitch of clothing to much comedic effect. The point is, though, that once again Central Park is depicted as a completely unsafe, alien landscape that is dangerous to all “normal” people – once again a far cry from its original perception or intended use.

A good example of the third characterization of the park, as simply a tree lined extension of the city around it is in “Marathon Man”, 1975, directed by John Schlesinger. In this film Dustin Hoffman plays a somewhat alienated graduate student that is training for the New York Marathon by running around the reservoir in Central Park. While the footage shot in the park is limited it is interesting for two reasons. The shots of Hoffman running show the park to be at the very least a functional landscape, a place that people can use for exercise and recreation. It is also notable for its last scene, which takes place in one of the century old pumping stations that are on either side of the reservoir. In it the evil Nazi Laurence Olivier is brought to justice, he is shot by Hoffman while being made to ingest the fortune in diamonds that he has murdered so ruthlessly to reclaim. Yet another killing in the park, but an interesting statement that it occurs only a few hundred yards from the townhouses of some of the most wealthy people in the world.

A good example of the third characterization of the park, as simply a tree lined extension of the city around it is in “Marathon Man”, 1975, directed by John Schlesinger. In this film Dustin Hoffman plays a somewhat alienated graduate student that is training for the New York Marathon by running around the reservoir in Central Park. While the footage shot in the park is limited it is interesting for two reasons. The shots of Hoffman running show the park to be at the very least a functional landscape, a place that people can use for exercise and recreation. It is also notable for its last scene, which takes place in one of the century old pumping stations that are on either side of the reservoir. In it the evil Nazi Laurence Olivier is brought to justice, he is shot by Hoffman while being made to ingest the fortune in diamonds that he has murdered so ruthlessly to reclaim. Yet another killing in the park, but an interesting statement that it occurs only a few hundred yards from the townhouses of some of the most wealthy people in the world.

In “Eyewitness”, 1981 directed by Peter Yates, the park is the scene of a picnic shared by Sigourney Weaver and William Hurt. It is set near a ball field, where Weaver, astride a fine brown horse, meets Hurt, on a Harley Davidson. The park is seen as a convivial kinetic landscape, a living space in which people play ball, eat picnic lunches, and live out their lives. (Sometimes going for days without dancing, singing or being brutally murdered.) The park here is a place where we could picture ourselves, hanging out with friends, relaxed and not feeling threatened. The camera is friendly to the landscape with long shots of playing fields and distant trees surrounded by buildings. We can sense that this place is indeed a refuge form city around it, a common ground in which Weaver can enjoy anonymity from her career as well known television reporter and Hurt can escape the drudgery of his life as a custodian. And, of course, a place where anyone can fall in love with anyone, the ultimate democratic ideal.

Add to these two examples any of a half dozen Woody Allen movies that use the park as a backdrop for conversations between characters, including “Annie Hall”, “Hannah and Her Sisters” and “Bullets Over Broadway”. Mr. Allen exhibits a familiarity with park that most people have with their own front yards, which would make sense since Central Park is literally his.

All of these movies share an interpretive legacy, in each one the park is used specifically as a metaphor for the city that surrounds it. This subtle allegory evolves over time from the happy singing and dancing of Gene Kelly to the beleaguered wanderings of Jack Lemmon back to the joyous singing and dancing of Twyla Tharp, via Treat Williams et.al.. While it might be a stretch to discover a narrative flow over the course of these six decades it would be interesting to edit together a single movie of clips that use Central Park as a dramatic location. It would be enlightening to see how the portrayal of the park mirrored the popular conception of the city that surrounds it, how the way it was shot either enhanced its beauty or revealed a darker side.

It would also be nice to see it get top billing.